Virtual Concert

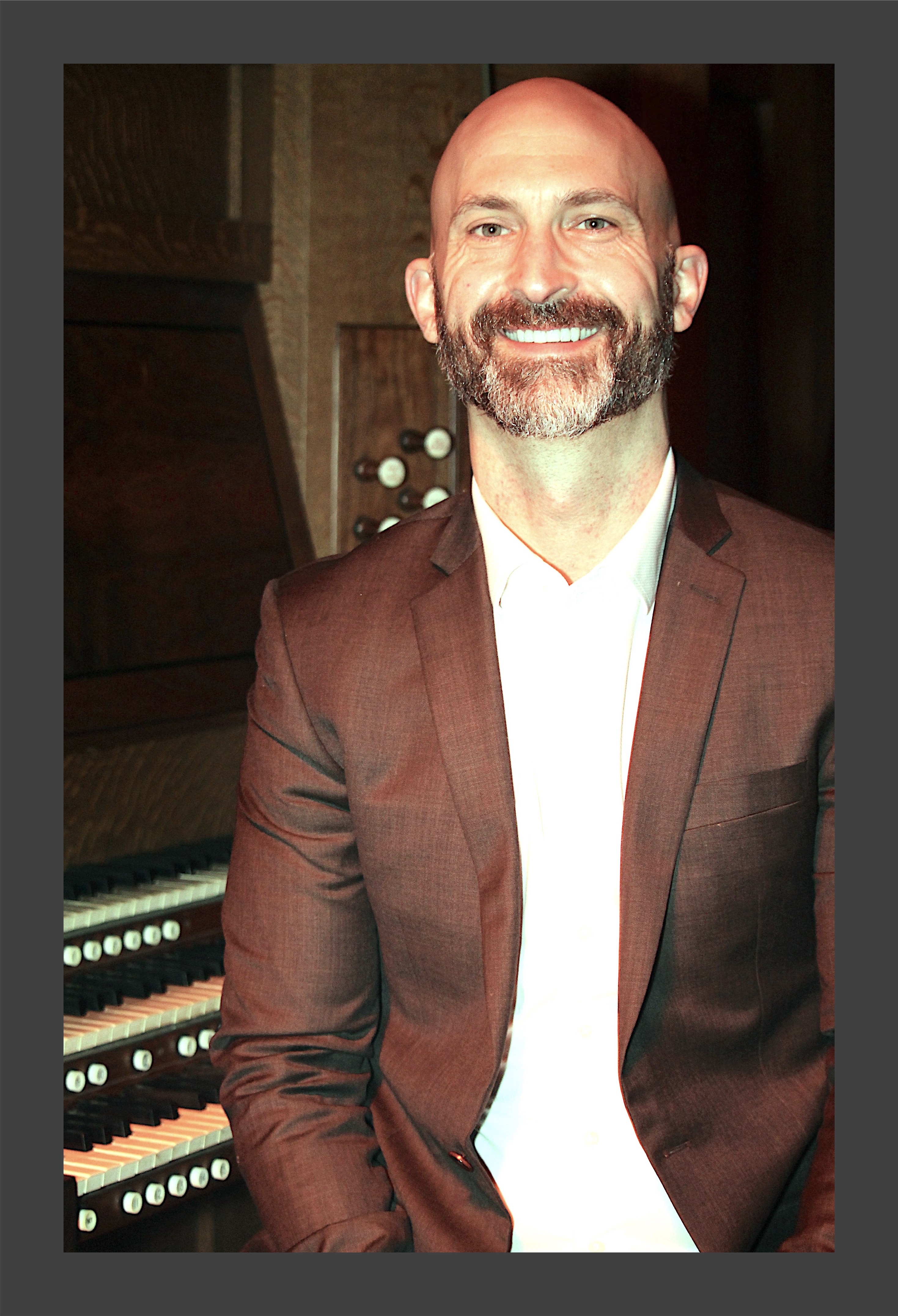

Saturday, March 12th will be a time to engage and be lifted up, soaking in a magnificence often only reserved for sacred settings and concert halls. On that day Piano by Nature will bring you music that has filled the Notre Dame Cathedral and soothed the human spirit, encompassing a multitude of nationalities, traditions, and styles that have been handed down through the ages. As Organist and Master of Choristers at the All Saints Church in Boston, Andrew Sheranian continually references the past to build on the future, and he explores music spanning the millennia directly alongside works from our own time. For his PBN virtual concert, he will share stories and music that bring to life these incredible traditions, enlightening us to a world in which he is a distinguished torchbearer and champion.

We in the North Country have had opportunities to experience Andrew’s stunning expertise through his earlier live performances at both the Essex Community Church and St. John’s Episcopal Church, and we now hope to introduce this incredible musician and scholar to a wider audience. For his Piano by Nature event, Andrew will be performing on two very special organs from different eras, giving us a glimpse into their unique sound, color, and structural properties. We are particularly grateful to Zoom for allowing us the opportunity to hear both of the organs side-by-side in their home at the All Saints Church in Boston. We hope you will take a moment to learn more about the organs here and here.

His PBN concert repertoire encompasses composers from four countries and an over three-century span of music. It will also highlight a glorious lesser-known work by Florence Price–the first female African-American to earn national recognition for her compositions. Please visit Andrew’s youtube channel to listen to some of his amazing past performances.

Join us online Saturday, March 12th at 7PM EST for an inspired concert of traditionally rich music of both ancient and newer works performed by the extraordinary organist Andrew Sheranian. To join this free concert, make sure you are subscribed to the Piano by Nature email list, which you can join at the bottom of any page of our website and we will send you updates and the link needed for the concert closer to the date. See you there!

Plattsburgh’s amazing Benjamin Pomerance has given us a wonderful and insightful glimpse into Andrew Sheranian’s musical world in his latest Lake Champlain Weekly article (February 16, 2022 issue) entitled “The Playground.” Please enjoy! Click images to enlarge or you may read or download PDF version here.

You can also read another nice article about Andrew Sheranian from Boston blog-writer David Patterson here (from The Boston Musical Intelligencer, Nov. 25, 2018).

Andrew Sheranian Biography

Since 2010, Andrew Sheranian has been Organist and Master of Choristers at the Parish of All Saints, Ashmont in Boston, a church known for its commitment to excellence in liturgy and music. His duties at Ashmont include recruiting, training, and conducting the Choir of Men and Boys, as well as playing the parish’s two pipe organs: C.B. Fisk Opus 103 of 1995 and Skinner Opus 708 of 1929, the latter installed in 2015 during Mr. Sheranian’s tenure.

Prior to Ashmont, Mr. Sheranian served seven years as Organist and Choirmaster at Christ’s Church in Rye, New York, working with a large semi-professional choir of adults, teens, boys, and girls. Before that, Mr. Sheranian was enrolled at Yale University through the Institute of Sacred Music, where he completed his Master of Music degree. While at Yale, Mr. Sheranian was the Fellow in Church Music at Christ Church New Haven, working alongside Martin Jean and Robert Lehman. His undergraduate training was completed at the New England Conservatory of Music, under the tutelage of William Porter.

As a recitalist, Mr. Sheranian has performed at major venues in Boston, New York City, New Haven, Salt Lake City, and many other locations in the United States and abroad. In February of 2006, Mr. Sheranian undertook a concert tour of Japan, playing recitals at Suntory Hall in Tokyo, and Minato Mirai Hall in Yokohama. In 2017, he was granted a four-month sabbatical from his post at Ashmont, which was spent observing collegiate and cathedral choirs in England and Germany.

A lifelong disciple of Johann Sebastian Bach, Mr. Sheranian is also the founding director of The Bach Project, a baroque ensemble of instrumentalists and singers aiming to perform the full spectrum of Bach’s music in performances at All Saints’ Ashmont. Mr. Sheranian is a member of the Association of Anglican Musicians, and has served as a Regional Chair of that organization. In his free time, he works to maintain an active YouTube channel, which includes performances on piano and organ.

Until the pandemic intervened, St. John’s Church in Essex, NY provided an annual choir camp for seven years for the choir boys of All Saints Church, Ashmont in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Under the leadership of their choir master and music director, Andrew Sheranian, the boys travelled to Essex for a choir camp that involved working on vocal and liturgical skills every morning and Adirondack outings and social activities for the remainder of each day.

At All Saints Church in metropolitan Boston, the boys are involved in an intensive year-round program under the direction of Mr. Sheranian. His leadership skills give the boys a deep understanding of choral music as he instructs them in all the skills needed to produce the beautiful music that enriches their Sunday worship. He is also the key to the educational experiences that the boys are provided in their carefully structured weekly program of study, recreation, and musical instruction at their home church. Because of their participation in the choir at All Saints, the boys learn responsibility and dedication as well as the tools to create high-quality choral music and are encouraged to excel in all areas of their lives.

Thanks to the dedication of Andrew Sheranian, the choir boys of All Saints Church are enriched in all areas of their lives as they grow into responsible and high-achieving young men.

The Program

Suite No. 1 – Florence Price (1887-1953)

1. Fantasy 2. Fughetta 3. Air 4. Tocatto

Sarabande for the 12th day of any October (from Partita, 1971) – Herbert Howells (1892-1983)

Scherzo (Opus 2) – Maurice Duruflé (1902-1986)

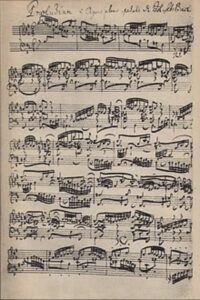

Prelude and Fugue in B minor (BWV 544) – Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

FLORENCE BEATRICE PRICE (1887-1953)

Rae Linda Brown University of California (included in score)

Florence Irvine Beatrice Smith Price (9 April 1887-3 June 1953) is the first African-American woman composer to earn national recognition. Born in Little Rock, Arkansas, Price was Influenced by her Southern roots, particularly by the culturally, socially, and politically sophisticated middle class Black community in which she was raised. Price’s father, Dr. James H. Smith, was Little Rock’s first Black dentist. An enterprising man, Smith was also an inventor of some promise, a published author, and during the Reconstruction years, he was active politically on the state and local levels. Price’s mother, Florence Irene Gulliver Smith, was an elementary school teacher before her marriage to Dr. Smith. After her children were born, she worked as a secretary for the Black-owned International Loan and Trust Co., and she was a successful businesswoman. She owned a restaurant, the Flora Cafe, and she actively bought and sold real estate.

Price was educated in the Black public schools of Little Rock, graduating from Capitol Hill School in 1902 at the age of fourteen. She received her first musical training from her mother and was presented in her first public recital at the age of four (the occasion was a visit to the Smith home by the distinguished Black concert pianist John “Blind” Boone). By the time Price was eleven she had sold her first composition to a publisher. In 1903, at the age of 15, Price was enrolled at the New England Conservatory of Music. She matriculated for three years, graduating in 1906 with an Artist’s Diploma in organ and a Teacher’s Diploma in piano. The curriculum for organ students was particularly demanding and comprehensive. In addition to preparing advanced students for concert performance, the program was designed to train church organists and choir directors.

At this time, organists could always find good work. Church positions requiring well-trained organists were becoming more plentiful, and prior to “sound pictures,” theatre organists who played classical repertoire and popular music, and who could improvise, were in demand. For the three years that Price matriculated at the Conservatory she studied organ with Henry M. Dunham, the chairman of the organ department. She also took courses in choir training and accompaniment and as an advanced student she received instruction in orchestral score reading and practice in reducing full orchestral accompaniments (both the wind and string parts) to the organ. This skill was particularly useful for church organists, who were expected to adapt choral and orchestral scores to the organ for performances. In addition, until the New England Conservatory orchestra was fully developed, Price and other advanced organ students were called upon to help out in orchestral rehearsals and in performance by playing the missing wind parts. Only the best students were given an opportunity to perform recitals at the Conservatory, and programs indicate that Price was among the few chosen students to perform regularly. In her third year at the Conservatory she played four times on the evening recital series for advanced students, including the concluding number–Henry M. Dunham’s Sonata in G-Minor on the commencement concert program.

Throughout her career Price maintained various organist positions, and she composed sacred music for church use, including incidental music for preludes and offertories, an organ sonata, an organ suite, choral music, and solo vocal music. She was also quite an accomplished theater organist, accompanying silent films in movie theaters in Chicago. Price began her formal training in composition and counterpoint at the New England Conservatory with Wallace Goodrich and Frederick Converse. She also studied composition with George Whitefield Chadwick, the Conservatory director and an eminent composer, who, after seeing the score of her first symphony, offered the young composer a scholarship to study in his private studio.

After graduation, Price returned home to teach music at the Cotton Plant-Arkadelphia Academy in Cotton Plant, Arkansas (1906-1907), and at Shorter College (1907-1910) in North Little Rock. From 1910-1912 she headed the music department at Clark University in Atlanta. In 1912, after marrying Thomas J. Price, a distinguished lawyer, Florence Price and her family settled in Chicago in 1927. It was here that Price established her career as a well-respected church organist, concert pianist, studio teacher, and a nationally acclaimed composer. In 1932 Price achieved national recognition when she won first prize in the Wanamaker Music Composition Contest for her Symphony in E Minor. With the Symphony’s premiere in June, 1933, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Frederick Stock, Price became the first African-American woman to have an orchestral work performed by a major American orchestra. Her Piano Concerto in One Movement, with the young, talented Black pianist Margaret Bonds, was performed the following year with the Woman’s Symphony Orchestra of Chicago, Ebba Sundstrom conducting. In 1940 the Michigan W. P. A. Orchestra, conducted by Walter Poole, premiered her Symphony in C Minor.

Price composed over 300 works. In addition to her orchestral music, she composed chamber works, art songs, piano and organ music, and she arranged instrumental and vocal versions of Spirituals. Her most well-known Spiritual arrangement, My Soul’s Been Anchored in De Lord, was recorded by Marian Anderson, Ellabelle Davis, and Leontyne Price. A versatile composer, Price also wrote popular music and orchestrated vocal pieces for WGN radio, which had a weekly broadcast of choral and solo vocal music. Price died in 1953 after receiving many accolades during her career. She won composition contests, performances of her works earned good press comments, and her teaching pieces, published by major companies including G. Schirmer, Theodore Presser, McKinley, Gamble Hinged, and Carl Fischer, were in demand. While maintaining a career primarily as a teacher and composer, Price also played numerous piano concerts, including much of her own music. In Chicago’s Black community she was also widely sought as a lecturer. Price’s musical style is often conservative, reflecting the romantic, nationalist style of the 1920s-1940s. Much of her instrumental music reflects also the influence of her cultural heritage, incorporating Spirituals, Spiritual-like themes, and characteristic dance music within classical forms.

A LITTLE MORE ABOUT FLORENCE’S LIFE

Racial tensions were high in the South, so Price initially had to pretend to be Mexican at school to escape the prejudices people had toward African Americans at this time. She turned her focus to composition and counterpoint while studying with composers George Chadwick and Frederick Converse at the conservatory. She graduated in with honors in 1906, having written her first string trio and symphony while completing her teaching certificate and artist diploma.

Racial tensions were high in the South, so Price initially had to pretend to be Mexican at school to escape the prejudices people had toward African Americans at this time. She turned her focus to composition and counterpoint while studying with composers George Chadwick and Frederick Converse at the conservatory. She graduated in with honors in 1906, having written her first string trio and symphony while completing her teaching certificate and artist diploma.

Price began teaching when she finished school, and soon after married. In 1927, as the social climate became more dangerous in the South, Price and her husband relocated to Chicago where her compositional career took off. She spent many of her early years in Chicago studying languages and liberal arts subjects at local conservatories and colleges and studying composition and orchestration with leading teachers in the city.

Even in the North, segregation and discrimination were inescapable. It was not uncommon for African Americans to be turned away from performing certain venues just because of their race. She found a community for herself when she joined the Chicago Music Association (CMA), which helped provide performance venues for African American musicians that were denied access to major concert halls.

Financial struggles led to Price’s divorce, which left her a single mother of two young girls in the city. She soon moved in with her pianist friend, Margaret Bonds. Together, Price and Bonds submitted compositions for Wanamaker Foundation Awards. Price won first prize for her Symphony in E minor and third for her piano sonata. The Chicago Symphony premiered the symphony in 1933, making Florence Price the first black female composer to have their piece performed by a major symphony orchestra.

As a single woman, she supported herself by publishing and selling her piano works under the pseudonym “Vee Jay”. She also orchestrated and played organ for WGN radio in addition to playing piano with regional ensembles such as the Michigan WPA Symphony, the Forum String Quartet, and the Chicago Chamber Orchestra. She also served as Recording Secretary of the CMA for a term.

Price wrote a large variety of pieces, including art songs, works for violin, organ, and piano, spiritual arrangements, chamber pieces, four symphonies, three piano concertos, and a violin concerto. Her style was heavily influenced by black melodies and rhythms, regardless of her training in European style composition. She took inspiration from African American church music and spirituals and weaved in traditional European Romantic techniques to create truly unique works with rich melodies and interesting rhythmic patterns.

Florence Price passed of a stroke at 66 in Chicago. With the changing times after her death, her music was overshadowed by new musical styles and some of her work was lost. In recent decades, her music has been revived by the Women’s Philharmonic, the New Black Repertory Ensemble, and various other women and African American centric ensembles and artists around the country. With each performance and remastering, the musical world is developing a new appreciation for her contribution to 20th century repertoire. (Source: “Florence Price: Once Overlooked, Now Rediscovered” by Kim Smallwood)

Herbert Howells

Herbert Howells (1892-1983) was one of the most significant English composers of the 20th century. His contribution to the musical repertoire of the Anglican church is immeasurable, and his organ works, are all classics in their own right.

Herbert Howells (1892-1983) was one of the most significant English composers of the 20th century. His contribution to the musical repertoire of the Anglican church is immeasurable, and his organ works, are all classics in their own right.

The stark, almost neo-classical nature of “Partita” probably comes as something of a shock to anyone familiar with the Howells of the first set of Psalm Preludes. Originally entitled “Sonata in Division”, it became “Partita” between its completion at the beginning of September 1971 and its presentation on the 28th of September to its dedicatee, The Rt. Honorable Edward Heath Prime Minister.

Many years earlier, Howells had promised to write Heath (then organ scholar at Balliol College Oxford) a piece should he ever become Prime Minister. Almost as soon as Heath arrived in Downing Street in 1970, Howells began writing.

By definition, a “saraband” is a stately court dance of the 17th and 18th centuries resembling the minuet. The music for the saraband is in slow triple time with accent on the second beat of the bar. In this respect, Howells’ “Sarabande”, which is the 4th movement of the “Partita” is a work admirably fits the definition. Notice also the influence of composers like the great Tudor master, Thomas Tallis. It was the combination and juxtaposition of old and new that was so much a part of the music of Howells. (Source: contrebombarde.com)

Herbert Howells: Partita

The Partita, composed in 1971, is inscribed “For the Rt Hon. Edward Heath, M.P., Prime Minister.” Its five movements enjoy the almost improvisatory freedom that is characteristic for Howells’ writing, yet they are bound together by a kind of cyclic feeling engendered by a fairly consistent use of an original mode: it descends from C to C as follows: C, B, B flat, G, F sharp, E, E flat, C. The Partita exploits both the melodic and harmonic implications of the mode.

(iv) Sarabande for the 12th day of any October: October 12th was the birthday of Ralph Vaughan Williams, and Dr Howells’ Sarabande gracefully suggests in its title that no year should be without its recollection of the G. O. M. of English music. Its ambivalent harmonies, which finally come to rest in E major, certainly evoke R.V.W. (Source: Felix Aprahamian, 1977)

Maurice Gustave Duruflé

Maurice Gustave Duruflé, French, (11 January 1902 – 16 June 1986) was a French composer, organist, musicologist, and teacher.

Maurice Gustave Duruflé, French, (11 January 1902 – 16 June 1986) was a French composer, organist, musicologist, and teacher.

Duruflé was born in Louviers, Eure in 1902. He became a chorister at the Rouen Cathedral Choir School from 1912 to 1918, where he studied piano and organ with Jules Haelling, a pupil of Alexandre Guilmant. The choral plainsong tradition at Rouen became a strong and lasting influence. At age 17, upon moving to Paris, he took private organ lessons with Charles Tournemire, whom he assisted at Basilique Ste-Clotilde, Paris until 1927. In 1920 Duruflé entered the Conservatoire de Paris, eventually graduating with first prizes in organ with Eugène Gigout (1922), harmony with Jean Gallon (1924), fugue with Georges Caussade (1924), piano accompaniment with César Abel Estyle (1926) and composition with Paul Dukas (1928).

In 1927, Louis Vierne nominated him as his assistant at Notre-Dame. Duruflé and Vierne remained lifelong friends, and Duruflé was at Vierne’s side acting as assistant when Vierne died at the console of the Notre-Dame organ on 2 June 1937, even though Duruflé had become titular organist of St-Étienne-du-Mont in Paris in 1929, a position he held for the rest of his life. In 1930 he won a prize for his Prélude, adagio et choral varié sur le “Veni Creator”, and in 1936 he won the Prix Blumenthal.In 1939, he premiered Francis Poulenc’s Organ Concerto (the Concerto for Organ, Strings and Timpani in G minor); he had advised Poulenc on the registrations of the organ part. In 1943 he became Professor of Harmony at the Conservatoire de Paris, where he worked until 1970; among his pupils were the revered organists Pierre Cochereau, Jean Guillou and Marie-Claire Alain.

In 1947 he completed probably the most famous of his few pieces: the Requiem op. 9, for soloists, choir, organ, and orchestra. He had begun composing the work in 1941, following a commission from the Vichy regime. Also in 1947, Marie-Madeleine Chevalier became his assistant at St-Étienne-du-Mont. They married on 15 September 1953 (Duruflé’s first marriage to Lucette Bousquet, in 1932, ended in civil divorce in 1947 and was declared null by the Vatican on 23 June 1953.) The couple became a famous and popular organ duo, going on tour together several times throughout the sixties and early seventies.

Duruflé was highly critical of his own compositions and published only a handful of works, often continuing to edit after publication. The result of this perfectionism is that his music, especially his organ music, tends to be well polished, and is still frequently performed in concerts by organists around the world.

Duruflé was highly critical of his own compositions and published only a handful of works, often continuing to edit after publication. The result of this perfectionism is that his music, especially his organ music, tends to be well polished, and is still frequently performed in concerts by organists around the world.

Duruflé and his wife were musically conservative. In 1969 they attended a “jazz mass” at St-Étienne-du-Mont. Marie-Madeleine was visibly upset by the experience, and Duruflé called it a scandalous travesty.

Duruflé suffered severe injuries in a car accident on 29 May 1975, and as a result he gave up performing; indeed he was largely confined to his apartment, leaving the service at St-Étienne-du-Mont to his wife Marie-Madeleine (who was also injured in the accident). He died in a clinic at Louveciennes (near Paris) in 1986, aged 84, never having fully recovered from the accident. (Source: Wikipedia)

Scherzo, Op. 2, 1926

Maurice Duruflé came from a long line of French organ virtuosi who composed mainly for their instrument but also contributed beautiful works to the symphonic repertoire. He enjoyed an extensive performing and teaching career and was a contemporary of Stravinsky and Britten. Duruflé remained conservative and reclusive in his life and his musical approach, with strong affinity for Gregorian chant and traditional harmonies. The Scherzo, Op. 2 is his earliest work for organ. The piece opens with other-worldly sustained chords and quickly moves into more intricate and improvisatory passages, modulating several times through the thematic development. (Source: Seattle Symphony)

Johann Sebastian Bach

The music of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) has been revered by listeners, churchgoers, and musicians of all stripes the world over for good reason: it is technically superb, artistically impeccable, symbolically rich, and emotionally satisfying, and performers find it among the most demanding music there is.

The music of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) has been revered by listeners, churchgoers, and musicians of all stripes the world over for good reason: it is technically superb, artistically impeccable, symbolically rich, and emotionally satisfying, and performers find it among the most demanding music there is.

Bach was born in Eisenach, Germany, into a devout Lutheran family of strong musical bent (and he extended this musical tradition to his children). An exceptional keyboard performer, he also played violin, and was even in his teens an outstanding organist; in his maturity he was respected as perhaps the best organist at least in Germany if not the world. Of the five major positions he held, three were as a church musician (at Arnstadt, 1703-1706, Mülhausen, 1707-1708, and Leipzig), meaning that he served variously as a church organist, choir director, and composer. At Arnstadt the 18-year-old Bach also began a tangent of his career as an organ inspector, tester, and exhibitor—work for which he would be sought through the rest of his life. At Weimar, 1708-1717, he was primarily a music teacher to the duke’s nephew, a court organist, chamber musician, and also a church organist and composer. At Anhalt-Cöthen, 1717-1723, in the completely secular position of Kapellmeister, he composed primarily for the elector and his instrumentalists. But he also was raising a family there, so he created extended didactic works systematically laid out to train young students, including his own children. Bach’s works from the Cöthen years range through all instrumental genres (and a few songs) except for organ: suites; sonatas and concertos; collections of educational works such as the clavier books for his wife, Anna Magdalena, and his son Wilhelm Friedemann; two- and three-part keyboard inventions; and the preludes and fugues comprising Book I of the Well-Tempered Keyboard.

By far Bach’s longest employment was at Leipzig, from 1723 until his death. Leipzig was a bastion of Lutheranism, and the city government was a de facto voice of church policy. Here, as the town council’s sixth choice for what was essentially a civic job—Director of Music for the city—Bach was obliged to provide, direct, and supervise music in the city’s two major churches, alternating between Thomaskirche and Nikolaikirche, and at civic events, as well as at festivals at the church at Leipzig University. His “day job” was as Kantor (third in seniority) at St. Thomas School, where he was responsible for teaching singing and music skills to the boys, preparing them to perform the music in church services, and generally assisting with supervising their daily activities. He was originally required to teach subjects other than music, such as Latin and mathematics, but he quickly found a replacement whom he paid to take over those classes. For a period he also served as director of the collegium musicum at Leipzig University. Not surprisingly, because he needed music every week for the city’s two important churches, he was continually composing sacred works. The great majority of his cantatas are from this period, as are the passions, the Christmas and Easter oratorios, the Mass in B minor, the motets, and again collections of pedagogical works such as a portion of the Clavier-Übung and the Art of Fugue.

By far Bach’s longest employment was at Leipzig, from 1723 until his death. Leipzig was a bastion of Lutheranism, and the city government was a de facto voice of church policy. Here, as the town council’s sixth choice for what was essentially a civic job—Director of Music for the city—Bach was obliged to provide, direct, and supervise music in the city’s two major churches, alternating between Thomaskirche and Nikolaikirche, and at civic events, as well as at festivals at the church at Leipzig University. His “day job” was as Kantor (third in seniority) at St. Thomas School, where he was responsible for teaching singing and music skills to the boys, preparing them to perform the music in church services, and generally assisting with supervising their daily activities. He was originally required to teach subjects other than music, such as Latin and mathematics, but he quickly found a replacement whom he paid to take over those classes. For a period he also served as director of the collegium musicum at Leipzig University. Not surprisingly, because he needed music every week for the city’s two important churches, he was continually composing sacred works. The great majority of his cantatas are from this period, as are the passions, the Christmas and Easter oratorios, the Mass in B minor, the motets, and again collections of pedagogical works such as a portion of the Clavier-Übung and the Art of Fugue.

Prelude and Fugue in B-minor, BWV 544

One of only a handful of organ prelude/fugue sets Bach wrote in Leipzig, BWV 544 has many memorable features. The prelude is among the most dramatic, featuring the powerful role of the pedals, which set German Baroque organ music apart from that of other nations. The prelude begins with a downward cascade that is soon met by a syncopated pedal figure of upward octave leaps. After a development of this opening topic, a new, lighter idea is given in the manuals. The two then tussle through different keys before the first idea returns to end the prelude.

After the rhythmic drive and harmonic tensions of the prelude, the fugue subject seems solid and trustworthy. Its regular, even notes move upward and back down again over a modest range. Gone are the syncopations and flashes of high drama; the pedals are generally assimilated more comfortably into the ensemble. As in the prelude, there is a lighter section for manuals. The return of the pedals is neatly prepared harmonically; now they have distinct activity, urging the drive to the conclusion. (Source:“BACH: PRELUDE AND FUGE IN B-MINOR” by Judith Eckelmeyer, Excerpted from Program Notes: November 21, 2014: Bach by Candlelight)

There is a good chance that Bach played this impressive piece for the first time in St Paul’s Church in Leipzig. That is where, on 17 October 1727, the university held a memorial service for the recently departed Christiane Eberhardine der Starke, who was the Electress of Saxony and the Queen of Poland. For this occasion, Bach wrote ‘funeral music in Italian style’: the cantata Laβ, Fürstin, laβ noch einen Strahl, BWV 198. During the ceremony, Bach played the organ himself. He opened with a prelude and ended with a fugue, and although nobody can prove it, it seems highly likely that it was this piece. It exudes the same atmosphere as the funeral music and is written in the same key of B minor. In those days, B minor was described as bizarre, listless and melancholy. And Bach used it more often for stately and mournful occasions, such as the aria ‘Erbarme dich’ from the St Matthew Passion, for example.

The despair is almost tangible in the prelude. Bach comes straight to the point with a melancholy lament, which is followed by great leaps in the pedal, repetitive and stubborn, as if you have to keep reminding yourself of what has happened. The whole piece seems to be filled with deep emotion. The fugue, logically, is more rational, although it is no less ingenious. Bach investigates every possibility of the relatively easy to sing theme. On the way to the end, when the pedal returns after a long absence, he adds a second element – once again with relatively large leaps – and so works towards a hopeful ending. (Source: Netherlands Bach Society)

Please consider sending a donation to Piano by Nature to help us continue to support our artists and deliver exceptional live music to the North Country and beyond. You can mail a check to Piano by Nature, 32 Champlain Ave., Westport, NY 12993. Or donate online through the Donate button below (using your Paypal account or credit card). If you have questions or ideas, feel free to call Rose at 518.962.8899. I’d love to hear from you.

This project is made possible with funds from the Decentralization Program, a regrant program of the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of the Office of the Governor and the New York State Legislature and administered by the Adirondack Lakes Center for the Arts. Made possible also, in part, by the Essex County Arts Council Cultural Assistance Program Grant supported by the Essex County Board of Supervisors.