PROGRAM

A program of works primarily by black composers, both women and men. The recital honors their voices, and puts them in dialogue with canonic works by JS Bach and Franz Liszt.

Johann Sebastian Bach “Prelude and Fugue in C Major, Book 2”

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson “Toccata”

(Margaret Bonds “Troubled Water”) TBA

Regina Harris Baiocchi- “Azuretta”

Regina Harris Baiocchi- “Listen, My Husband is not a Hat!”

Franz Liszt “Ballade No. 2”

Florence Price “Sonata in E Minor”

“I was specifically thinking about the influence of the spiritual in Price’s sonata, and how spirituals were an adaptation of enslaved Africans who found themselves restricted from communicating in their native tongue. I was also thinking of how Liszt adapted a greek myth for his Ballade, and how Baoicchi adapted literature into her work. If Margaret Bonds finds itself on the program in the end, that is also an adaptation of a real spiritual for piano.” —Donald Allen Lee

This Piano by Nature concert was featured in Lake Champlain Weekly in the article “An American Conversation.” Click images to enlarge or read here.

On March 13th, Piano by Nature is thrilled to present a program of some works you may know, and many works you might not. Donald Lee has selected a stunning program of works covering a span from the 1700s to the present, including musical innovators who have brought an infusion of bold and original new thought into the world of music. This exquisite concert features composers who were trail-blazers—the first African American pianist to solo with a symphony orchestra; the first African American woman to write for a symphony orchestra; a composer who pioneered the idea of consolidating classical, jazz, spiritual, and pop styles in the 1970s; a pianist who invented new horizons of style and harmony, along with the symphonic poem; and finally, Papa Bach, who successfully blended the use of diatonicism with chromaticism to solidify the Western musical system we have today. All of these composers successfully adapted to their unique challenges in order to produce voices of groundbreaking significance. Listen here for Donald’s verbal notes on the program.

On March 13th at 7:00 PM Eastern Standard Time, Piano by Nature will present a zoom concert free of charge to all that wish to join us, including a live appearance of Donald Allen Lee. All you have to do is sign-up to our email list located on our website pianobynature.org (scroll to the bottom of the page!), and then ‘press play’ on the link we send you. And if you cannot join us on the 13th, or if you’d like to watch it again, just go to our website and enjoy the link as many times as you want for 2 weeks after the zoom event. We hope to see you on the 13th and look forward to experiencing this very special event together!

Watch and listen to some examples of Donald’s playing below!

If you enjoy this concert please consider sending a donation to Piano by Nature.

You can mail a check to Piano by Nature, 32 Champlain Ave., Westport, NY 12993.

Or donate online through the Donate button below (using your Paypal account or credit card).

About Donald Lee III

Donald Lee III received his Master’s Degree in Piano from CCM, where he was a Yates Scholar and student of Awadagin Pratt. He has won numerous awards and prizes including MTNA, James Madison University Concerto Competition, Harold Protsman Classical Period Competition, and the Eastern Music Festival Concerto Competition. He has made appearances as soloist with the James Madison University Symphony Orchestra in VA, as well as the Guilford Symphony Orchestra in NC.

Donald received his bachelor’s degree from James Madison University where he was a Presser Scholar and student of Dr. Eric Ruple. He also received instruction from Brazilian pianist, Luiz de Moura Castro during his undergraduate years. Having attended the Eastern Music Festival, the Chautauqua Institution, the Art of the Piano festival, and the Wintergreen Festival (which he was invited to attend after winning the VMTA Piano Concerto Competition), he has had the opportunity to perform in masterclasses for renowned pianists such as Boris Slutsky, Jim Giles, Paul Schenly, and Yong Hi Moon to name a few.

In August 2018, Donald joined the faculty of the Kentucky State University as an Assistant Professor of Piano. Also an accomplished gospel musician, he continues to serve as Keyboardist to New Jerusalem Baptist Church in Cincinnati, OH. This fall, he will be returning to CCM to pursue an Artist Diploma.

A Little About The Composers

Regina Harris Baiocchi (b. 1956) is a poet, author, and composer whose music has been performed by Detroit and Chicago Symphony orchestras, US Army Band, and internationally-acclaimed artists. Performances include concerts in Paris, Rome, and Bari, Italy, as part of Festival Incontri Musicali di Musica Sacra, and in Turkey and Unna, Germany at the Women Composers’ Library. Regina has written music for symphony orchestra; a libretto and one-act opera; hand drum concerto; marimba concerto; ballet; chamber music; liturgical and secular music; and vocal and instrumental, including for pipe organ.” (3arts.org)

Margaret Bonds (1913-1972) was the first black guest to play with the Chicago Symphony, and was an accomplished pianist as well as composer and teacher. Born in Chicago, Margaret Bonds grew up in a musical household, studying music first with her mother, Estelle C. Bonds, who was an organist. Musical life in the city of Chicago was also very rich, and Bonds had the chance to study piano and composition with Florence Price while she was in high school. Bonds earned her BM and MM from Northwestern University and earned her first prize for composition in 1932 (the Wanamaker Prize for her song “Sea Ghost”). In 1933, Bonds performed Price’s piano concerto with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Also, before leaving Chicago, Bonds opened the Allied Arts Academy.

In 1939, Bonds moved to New York, marrying Lawrence Richardson and attending Juilliard Graduate School the following year. In New York, Bonds (who kept her mother’s maiden name as her own for life) worked to advance black musicians and composers and organized a chamber society dedicated to supporting the work of black composers and musicians.

Bonds’ output consists mainly of vocal music, though she also wrote several large-scale musical theatre works, including Shakespeare in Harlem (1959). Leontyne Price commissioned and recorded several spirituals arranged by Bonds. (Christie Finn)

Florence Price (1887-1953) was an African-American classical composer, pianist, organist and music teacher. Price is noted as the first African-American woman to be recognized as a symphonic composer, and the first to have a composition played by a major orchestra.

She was born as Florence Beatrice Smith to Florence (Gulliver) and James H. Smith on April 9, 1887, in Little Rock, Arkansas, one of three children in a mixed-race family. Despite racial issues of the era, her family was well respected and did well within their community. Her father was a dentist and her mother was a music teacher who guided Florence’s early musical training. She had her first piano performance at the age of four and had her first composition published at the age of 11.

By the time she was 14, Florence had graduated as valedictorian (scholar) of her class. After high school, she later enrolled in the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts with a major in piano and organ. Initially, she passed as Mexican to avoid racial discrimination against African Americans, listing her hometown as “Pueblo, Mexico.” At the Conservatory, she studied composition and counterpoint with composers George Chadwick and Frederick Converse. Also while there, Smith wrote her first string trio and symphony. She graduated in 1906 with honors, and with both an artist diploma in organ and a teaching certificate.

Smith returned to Arkansas, where she taught briefly before moving to Atlanta, Georgia, in 1910. There, she became the head of the music department of what is now Clark Atlanta University, a historically black college. In 1912, she married Thomas J. Price, a lawyer. She moved back to Little Rock, Arkansas, where he had his practice. After a series of racial incidents in Little Rock, particularly a lynching of a black man in 1927, the Price family decided to leave. Like many black families living in the Deep South, they moved north in the Great Migration to escape Jim Crow conditions, and settled in Chicago, a major industrial city.

There, Florence Price began a new and fulfilling period in her composition career. She studied composition, orchestration, and organ with the leading teachers in the city, including Arthur Olaf Andersen, Carl Busch, Wesley La Violette, and Leo Sowerby. She published four pieces for piano in 1928. While in Chicago, Price was at various times enrolled at the Chicago Musical College, Chicago Teacher’s College, University of Chicago, and American Conservatory of Music, studying languages and liberal arts subjects as well as music. Financial struggles and abuse by her husband resulted in Price getting a divorce in 1931. She became a single mother to her two daughters. To make ends meet, she worked as an organist for silent film screenings and composed songs for radio ads under a pen name. During this time, Price lived with friends. She eventually moved in with her student and friend, Margaret Bonds, also a black pianist and composer. This friendship connected Price with writer Langston Hughes and contralto Marian Anderson, both prominent figures in the art world who aided in Price’s future success as a composer.

Together, Price and Bonds began to achieve national recognition for their compositions and performances. In 1932, both Price and Bonds submitted compositions for the Wanamaker Foundation Awards. Price won first prize with her Symphony in E minor, and third for her Piano Sonata, earning her a $500 prize. (Bonds came in first place in the song category, with a song entitled “Sea Ghost.”) The Chicago Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Frederick Stock, premiered the Symphony on June 15, 1933, making Price’s piece the first composition by an African-American woman to be played by a major orchestra. A number of Price’s other orchestral works were played by the WPA Symphony Orchestra of Detroit, the Chicago Women’s Symphony, and the Women’s Symphony Orchestra of Chicago.Price wrote other extended works for orchestra, chamber works, art songs, works for violin, organ anthems, piano pieces, spiritual arrangements, four symphonies, three piano concertos, and a violin concerto. Some of her more popular works are: “Three Little Negro Dances,” “Songs to a Dark Virgin”, “My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord” for piano or orchestra and voice, and “Moon Bridge”. Price made considerable use of characteristic African-American melodies and rhythms in many of her works. Her Concert Overture on Negro Spirituals, Symphony in E minor, and Negro Folksongs in Counterpoint for string quartet, all serve as excellent examples of her idiomatic work. Price was inducted into the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers in 1940 for her work as a composer. In 1949, Price published two of her spiritual arrangements, “I Am Bound for the Kingdom,” and “I’m Workin’ on My Buildin'”, and dedicated them to Marian Anderson, who performed them on a regular basis.

Even though her training was steeped in European tradition, Price’s music consists of mostly the American idiom and reveals her Southern roots. She wrote with a vernacular style, using sounds and ideas that fit the reality of urban society. Being a committed Christian, she frequently used the music of the African-American church as material for her arrangements. At the urging of her mentor George Whitefield Chadwick, Price began to incorporate elements of African-American spirituals, emphasizing the rhythm and syncopation of the spirituals rather than just using the text. Her melodies were blues-inspired and mixed with more traditional, European Romantic techniques. The weaving of tradition and modernism reflected the way life was for African Americans in large cities at the time. (Wikipedia)

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson (1932-2004) was an innovative American composer whose interests spanned the worlds of jazz, dance, pop, film, television, and classical music. Perkinson’s music has a blend of Baroque counterpoint; American Romanticism; elements of the blues, spirituals, and black folk music; and rhythmic ingenuity.

Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson was Afro-American. He was named after Afro-British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912). Perkinson’s mother was active in music and the arts as a piano teacher, church organist, and director of a theater company.

Perkinson attended the High School of Music and Art in New York City. After graduating from high school, he attended New York University. He later transferred to the Manhattan School of Music, where he studied composition with Vittorio Giannini and Charles Mills. He received bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the Manhattan School of Music.[2] He also studied with Earl Kim at Princeton University. He was on the faculty of Brooklyn College (1959–1962) and studied conducting in the summers of 1960, 1962, and 1963 in the Netherlands with Franco Ferrara and Dean Dixon and also learned conducting in 1960 at the Mozarteum in Salzburg. Perkinson cofounded the Symphony of the New World in New York in 1965 and later became its Music Director. He was also Music Director of Jerome Robbins’s American Theater Lab and the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Perkinson composed a ballet for Ailey entitled For Bird, With Love inspired by the music of jazz great Charlie Parker.[1]

Perkinson wrote a great deal of classical music, but was equally well-versed in jazz and popular music. He served briefly as pianist for drummer Max Roach’s quartet and wrote arrangements for Roach, Marvin Gaye, and Harry Belafonte. He also composed music for films such as The McMasters (1970), Together for Days (1972), A Warm December (1973), Thomasine & Bushrod (1974), The Education of Sonny Carson (1974), Amazing Grace (1974), Mean Johnny Barrows (1976), and the documentary Montgomery to Memphis (1970) about Martin Luther King Jr. In 1970 he wrote incidental music for at least one episode of the US television show Room 222. (Wikipedia)

Johann Sebastian Bach, (born March 21 [March 31, New Style], 1685, Eisenach, Thuringia, Ernestine Saxon Duchies [Germany]—died July 28, 1750, Leipzig), composer of the Baroque era, the most celebrated member of a large family of north German musicians.

Although he was admired by his contemporaries primarily as an outstanding harpsichordist, organist, and expert on organ building, Bach is now generally regarded as one of the greatest composers of all time and is celebrated as the creator of the Brandenburg Concertos, The Well-Tempered Clavier, the Mass in B Minor, and numerous other masterpieces of church and instrumental music. Appearing at a propitious moment in the history of music, Bach was able to survey and bring together the principal styles, forms, and national traditions that had developed during preceding generations and, by virtue of his synthesis, enrich them all. (Robert L. Marshall for ‘Britannica’)

Franz Liszt (1811–86) was a Hungarian composer, pianist and teacher who was one of the leading music figures of the Romantic movement, and the greatest piano virtuoso of his age. Liszt was born in Raiding and started learning the piano aged six. He gave his first public performance aged nine and soon became famed as a child prodigy. From 1839 to 1847 (a period known as Liszt’s Glanzzeit, or glory days) the adult Liszt gave more than a thousand concerts across Europe, creating the modern piano recital in terms of repertory, venue and performance style (he was also the first to use the word ‘recital’ in this way). Glanzzeit compositions include the ‘Paganini’ Studies, the ‘Transcendental’ Studies and his many remarkable transcriptions. In 1848 Liszt settled in Weimar, with works from this period including many symphonic poems (a genre he invented), the Faust-Symphonie, the B Minor Piano Sonata and numerous songs. In 1859 he moved to Rome and joined the Roman Catholic church, receiving the tonsure in 1865. Works written in Rome include the oratorios Die Legende von der heiligen Elisabeth and Christus. From 1869 he split his time between Rome, Weimar and Budapest, in Weimar holding his famous masterclasses (another form he invented) and in Budapest becoming the first president of the newly formed National Hungarian Royal Academy of Music in 1875.

Liszt was a musical innovator, not only through his transformative use of the piano but in many other areas, including his increasingly radical use of harmony. He was a fervent supporter of the music of others, using his celebrated recitals to champion works by composers including Bach, Handel, Schubert, Beethoven, Wagner and Berlioz. (“Franz Liszt” Royal Opera House)

A More In-Depth Look into African American Spirituals from the Library of Congress

A spiritual is a type of religious folksong that is most closely associated with the enslavement of African people in the American South. The songs proliferated in the last few decades of the eighteenth century leading up to the abolishment of legalized slavery in the 1860s. The African American spiritual (also called the Negro Spiritual) constitutes one of the largest and most significant forms of American folksong.

Famous spirituals include “Swing low, sweet chariot,” composed by a Wallis Willis, and “Deep down in my heart.” The term “spiritual” is derived from the King James Bible translation of Ephesians 5:19: “Speaking to yourselves in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody in your heart to the Lord.” The form has its roots in the informal gatherings of

African slaves in “praise houses” and outdoor meetings called “brush arbor meetings,” “bush meetings,” or “camp meetings” in the eighteenth century. At the meetings, participants would sing, chant, dance and sometimes enter ecstatic trances. Spirituals also stem from the “ring shout,” a shuffling circular dance to chanting and hand-clapping that was common among early plantation slaves. An example of a spiritual sung in this style is “Jesus Leads Me All the Way,” sung by Reverend Goodwin and the Zion Methodist Church congregation and recorded by Henrietta Yurchenco in 1970.

In Africa, music had been central to people’s lives: Music making permeated important life events and daily activities. However, the white colonists of North America were alarmed by and frowned upon the slaves’ African-infused way of worship because they considered it to be idolatrous and wild. As a result, the gatherings were often banned and had to be conducted in a clandestine manner. The African population in the American colonies had initially been introduced to Christianity in the seventeenth century. Uptake of the religion was relatively slow at first. But the slave population was fascinated by Biblical stories containing parallels to their own lives and created spirituals that retold narratives about Biblical figures like Daniel and Moses. As Africanized Christianity took hold of the slave population, spirituals served as a way to express the community’s new faith, as well as its sorrows and hopes.

Spirituals are typically sung in a call and response form, with a leader improvising a line of text and a chorus of singers providing a solid refrain in unison. The vocal style abounded in freeform slides, turns and rhythms that were challenging for early publishers of spirituals to document accurately. Many spirituals, known as “sorrow songs,” are intense, slow and melancholic. Songs like “Sometimes I feel like a motherless child,” and “Nobody knows de trouble I’ve seen,” describe the slaves’ struggles and identification the suffering of Jesus Christ. Other spirituals are more joyful. Known as “jubilees,” or “camp meeting songs,” they are fast, rhythmic and often syncopated. Examples include “Rocky my soul” and “Fare Ye Well.”

Spirituals are also sometimes regarded as codified protest songs, with songs such as “Steal away to Jesus,” composed by Wallis Willis, being seen by some commentators as incitements to escape slavery. Because the Underground Railroad of the mid-nineteenth century used terminology from railroads as a secret language for assisting slaves to freedom, it is often speculated that songs like “I got my ticket” may have been a code for escape. Hard evidence is difficult to come by because assisting slaves to freedom was illegal. A spiritual that was certainly used as a code for escape to freedom was “Go down, Moses,” used by Harriet Tubman to identify herself to slaves who might want to flee north. [note 1]

As Frederick Douglass, a nineteenth-century abolitionist author and former slave, wrote in his book My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) of singing spirituals during his years in bondage: “A keen observer might have detected in our repeated singing of ‘O Canaan, sweet Canaan, I am bound for the land of Canaan,’ something more than a hope of reaching heaven. We meant to reach the North, and the North was our Canaan.”

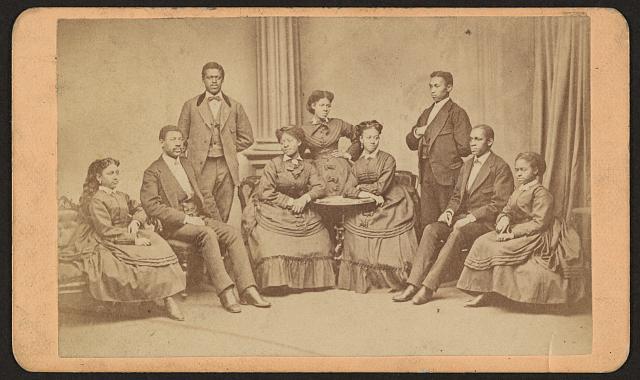

Detail from Jubilee Singers, Fisk University, Nashville, Tenn. Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsca-11008. The Fisk University Jubilee Singers helped to raise awareness of African American spirituals through concerts and recordings under the direction of John W. Work, Jr., the first African American to collect and publish spirituals. Photograph taken between 1870 and 1880.

The publication of collections of spirituals in the 1860s started to arouse a broader interested in spirituals. In the 1870s, the creation of the Jubilee Singers, a chorus consisting of former slaves from Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, sparked an international interest in the musical form. The group’s extensive touring schedule in the United States and Europe included concert performances of spirituals that were very well received by audiences. While some African Americans at the time associated the spiritual tradition with slavery and were not enthusiastic about continuing it, the Fisk University singers performances persuaded many that it should be continued. Ensembles around the country started to emulate the Jubilee singers, giving birth to a concert hall tradition of performing this music that has remained strong to this day.

The Hampton Singers of Hampton Institute (now Hampton University in Hampton, Virginia) was one of the first ensembles to rival the Jubilee Singers. Founded in 1873, the group earned an international following in the early and mid-twentieth century under the baton of its longtime conductor R. Nathaniel Dett. Dett was known not just for his visionary conducting abilities, but also for his impassioned arrangements of spirituals and original compositions based on spirituals. A cappella arrangements of spirituals for choruses by such noted composers as Moses Hogan, Roland Carter, Jester Hairston, Brazeal Dennard and Wendell Whalum have taken the musical form beyond its traditional folk song roots in the twentieth century.

The appearance of spirituals on the concert hall stage was further developed by the work of composers like Henry T. Burleigh, who created widely performed piano-voice arrangements of spirituals in the early twentieth century for solo classical singers. Follow the link to view sheet music for “A Balm in Giliad,” an example of a spiritual arranged by Burleigh. Marian Anderson’s 1924 rendition of “Go Down Moses,” is taken from an arrangement to Burleigh (select the link to listen to this recording).

![Detail from [Harry Thacker Burleigh, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing right]. Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-114982. Henry "Harry" Thacker Burleigh was a classical composer, arranger, and professional singer who arranged traditional spirituals for orchestra.](https://pianobynature.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/0003.jpg)

Detail from [Harry Thacker Burleigh, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing right]. Prints and Photographs Division, Reproduction Number: LC-USZ62-114982. Henry “Harry” Thacker Burleigh was a classical composer, arranger, and professional singer who arranged traditional spirituals for orchestra.

Many recordings of these rural spirituals, made between 1933 and 1942, are housed in the American Folklife Center collections at the Library of Congress. The collection includes such gems as “Run old Jeremiah,” a ring shout from Jennings, Alabama recorded by J. W. Brown and A. Coleman in 1934, which has a train-like accompaniment of stamping feet; and “Eli you can’t stand,” a spiritual underpinned by handclapping featuring lead singing by Willis Proctor recorded on St. Simon’s Island, Georgia in 1959. Many field recordings of spirituals are available online in this presentation, including the earliest known recording of “Come by here,” or as it is often called today, “Kumbaya,” sung by H. Wylie and recorded by folklorist Robert Winslow Gordon on a wax cylinder in 1926 (the middle of this recording is inaudible, probably due to deterioration of the cylinder). A curator talk on “Kumbaya” by folklorist Stephen Winick is available on this podcast.

The “white spiritual” genre, though far less well recognized than its “negro spiritual” cousin, encompasses the folk hymn, the religious ballad and the camp-meeting spiritual. White spirituals share symbolism, some musical elements and somewhat of a common origin with African American spirituals. In 1943, Willis James made this field recording of the Lincoln Park Singers performing “I’ll fly away,” which was composed by Albert E. Brumley, a white man. This field recording serves to illustrate the link between Black and white spirituals.

The genre of white spirituals came to light in the 1930s when George Pullen Jackson, a professor of German at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, published the book White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands (1933). The book was the first in a series of studies that highlighted the existence of white spirituals in both their oral and published forms, the latter occurring in the shape-note tune books of rural communities.

Black spirituals vary from white spirituals in a variety of ways. Differences include the use of microtonally flatted notes, syncopation, and counter-rhythms marked by handclapping in black spiritual performances. Black spiritual singing also stands out for the singers’ striking vocal timbre that features shouting, exclamations of the word “Glory!” and raspy and shrill falsetto tones.

Spirituals have played a significant role as vehicles for protest at intermittent points during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. During the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, spirituals as well as Gospel songs supported the efforts of civil rights activists. Many of the “freedom songs” of the period, such as “Oh, Freedom!” and “Eyes on the Prize,” were adapted from old spirituals. Both of these songs are performed by the group Reverb in a video of their concert at the Library of Congress in 2007. The movement’s torch song, “We Shall Overcome,” merged the gospel hymn “I’ll Overcome Someday” with the spiritual “I’ll Be all right.”

Freedom songs based on spirituals have also helped to define struggles for democracy in many other countries around the world including Russia, Eastern Europe, China and South Africa. Some of today’s well-known pop artists continue to draw on the spirituals tradition in the creation of new protest songs. Examples include Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song” and Billy Bragg’s “Sing their souls back home.” (Library of Congress: “African American Spirituals”)