PROGRAM

Sonatina Op. 100 * Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904)

Allegro risoluto – Larghetto – Scherzo (Molto vivace) – Finale (Allegro)

Second Sonata (composed 1914-1917) * Charles Ives (1874-1954)

I. Autumn II. In the Barn III. The Revival

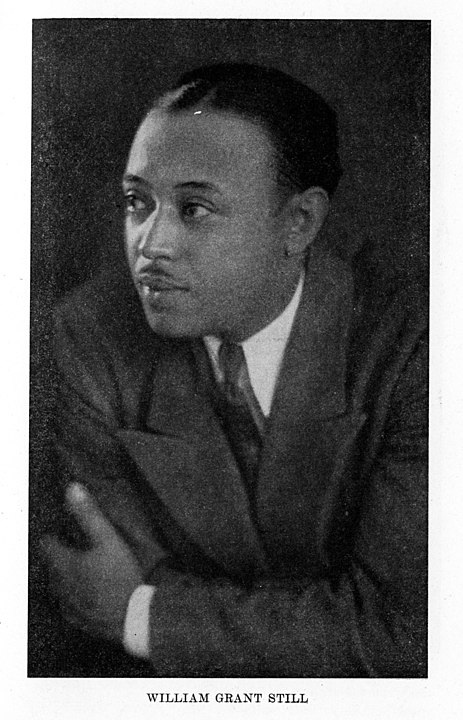

Three Pieces for Violin and Piano * William Grant Still (1895-1978)

Blues (arranged by Louis Kaufman)

Here’s One (arranged by Louis Kaufman)

Summerland

Sonata No. 3, Op. 108 * Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Allegro – Adagio – Un poco presto e con sentimento – Presto agitato

In late 19th-Century America, concert halls predominantly presented music following the European tradition, considered a high-class endeavor among promoters and concert-goers. Much of the so-called ‘new’ music being written and performed was still highly imitative of older Classical works similar to Haydn and Beethoven. The ‘New World’ at this time was still searching for its own modern style which had yet to be born. In 1893 Antonin Dvorak was brought from his homeland of Czechoslovakia to New York City to direct the National Conservatory of Music. He was recognized worldwide for his more modernist and nationalistic approach, liberally using folk material throughout his still lush and Romantic-style compositions. His task at the conservatory was nothing less than to help establish an authentic ‘American’ style that would shake-off the European dominance prevalent throughout American concert halls. While there, Dvorak befriended a young African-American student named Harry T.Burleigh who reputedly was singing old plantation songs while cleaning the Conservatory. Dvorak heard him and wanted to learn more, and Burleigh became instrumental in sharing and introducing classically trained artists to the uniquely American music of spirituals.

While there, Dvorak premiered his New World Symphony in 1893, which was received quite favorably and is considered one of the greatest symphonies of all time. Music of American Indians and African-American spirituals were a major source of inspiration for the work, and soon afterward Dvorak pronounced his conclusion:

“I am convinced that the future music of the country must be founded on what are called the Negro melodies. These can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition, to be developed in the United States. These beautiful and varied themes are the product of the soil. These are the folk songs of America and your composers must turn to them.”

This caused quite a stir at the time, but his observations inevitably helped America to shape a new national voice, and to look more within for its inspirations. At the time, Dvorak was advocating for the use of indigenous melody as compositional material, but with his advocacy also came appropriation, bringing up a whole host of prejudicial complications. Vanderbilt musicology professor Douglas Shadle has written a beautiful and concise article exploring this aspect, and I encourage you to read more on this important topic here.

This concert unites a group of composers who lived in similar eras and were indebted to each other’s influences in many different ways.

The link that connects all of the composers on our program is folk music. In the late 19th-Century, nationalism was on the rise, and the incorporation of recognizable folk elements and quotations from unique traditions became a dominant influence in western classical composition. Many 20th-Century composers from different countries looked to the use of folk music as inspiration for their music including Ralph Vaughn Williams, Bela Bartok, Igor Stravinsky, George Gershwin, Charles Ives, Antonin Dvorak, Bedrich Smetana, Percy Granger, Aaron Copland, Gustov Holst, Johannes Brahms, Manuel de Falla, William Grant Still, George Enescu, Zoltan Kodaly, and Frederic Rzewski to name a few.

For our program, we are exploring the relationships and influences of four composers: Johannes Brahms, Antonin Dvorak, Charles Ives, and William Grant Still.

Johannes Brahms, a 19th-Century inspiration for the remaining three, was an incredible music scholar, studying works of composers going back to the Renaissance, and crafting music from his intricate knowledge of the past. He was both a traditionalist and an innovator, and he also wrote unique and inspired arrangements of pre-existing Hungarian and German melodies. He was considered a titan of the European Romantic tradition.

Antonin Dvorak utilized the Bohemian melodic treasure trove of his homeland as source-material for his compositions. He then came to America and discovered spirituals, blues, and American Indian influences, proclaiming these to be the richest and most authentic veins to mine for a true American music. Johannes Brahms was supportive of fellow-European Antonin Dvorak, and introduced him to his publisher.

Charles Ives voraciously studied the forms and traditions of European classical music, including those of Dvorak and Brahms, and then combined that with his own unique and radical New England style (it is noted that he had a picture of Brahms in his music studio). Ives is often considered the most representative of American composers, utilizing American gospel, parlor songs, hymns, patriotic songs, and more to create mosaic-like works of both incredible accessibility and complexity. Recognizable fragments of these well-known (at the time) popular tunes are scattered throughout his works, creating a new and distinctly American texture and voice through innovations in form, rhythm, and harmony.

William Grant Still also studied the European traditions at Oberlin and the New England Conservatory, and in addition had many other influences including the music of his American peers Charles Chadwick, Horatio Parker, Amy Beach, and Edward MacDowell plus the French modernist Edgar Varese. He was the first African-American composer to premier a large orchestral work in 1931 called The Afro American Symphony, a work that deftly incorporated jazz, blues, and spiritual melodies within a more traditional classical form. Throughout his life he worked in many genres of the musical trade, delving into the pop and jazz worlds, orchestrating works for W.C. Handy, arranging for radio, and writing music for theatrical productions and film, but always remaining true to his first love of modern composition. Conductor Leopold Stokowski perhaps summed up William Grant Still best:

“In my opinion, William Grant Still is one of America’s great citizens, because his musical nature has given him the power to fuse into one unified expression our American music of today with the ancestral memories lying deep within him of African music. This blending into one stream of diverse racial cultural origins is most important to the future of our country. For the reason that we Americans from so many racial origins, we must find a way to harmonize them into one – in our cultural and economic existence, and in our conception of what is the good life that we can share. Still has succeeded in this to a remarkable degree – and this is what gives deep significance to his life and musical creation.”